Art Beyond Borders.

Marie Barras & Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

Among the preliminary results of the Visual Contagions project, one element brings together many clusters that are more international than others: many are works of art. These clusters of similar images, isolated by the machine from our three million images recovered from printed periodicals from the 1880s-1950s, cross even more borders than the others.

Art magazines, already, share more images with each other than all the periodicals in our corpus, on an international scale.

We have shown this in a previous chapter.

The factors of this more fluid circulation of art images are multiple.

--

Some works are reproduced in several magazines on the occasion of great international events: academic or modern art Salons (in particular the Secessions, spread throughout Europe after 1890 and particularly internationalized), Universal Exhibitions, exhibitions organized on the occasion of royal or imperial jubilees...

--

--

These shots reported by the algorithm were taken on the occasion of the Vienna Secession of 1904. The set highlights the work of the sculptor Franz Metzner ("Die Erde").

--

Another factor in the global circulation of images is the international art market.

From sale to resale, the works pass from one collection to another. With our tools and our corpus, we can quickly reconstruct what is called the provenance of certain works - for example, that of Greco's Laocoon, which travelled through Europe before ending up on the walls of the National Gallery of art of Washington. The National Gallery had to work without our tools to reconstruct the work's origin- but they may be able to use them for future provenance research!

--

We also found magazines that share the same pictures, probably commissioned from the same image dealers - or because two magazines are twins, like The Studio (London) and its transatlantic version International Studio published in New York.

--

Some images pass from one magazine to another, in a great regularity of exchanges between magazines. These networks suggest critical and commercial relations that were particularly solid between the wars: the magazines addressed the same merchants; they sometimes translated articles that had appeared in other countries, also taking the associated illustrations.

This circulation from one magazine to another can be the effect, as in the case of Picasso, of a gallery's monopoly on the production and distribution of the artist's work. The dealer only reproduces what he decides. For Picasso, during his lifetime, the reproductions authorized by his dealers were most often images of classical periods. Rarely were they illustrations of works that were too innovative[1].

--

--

Number of connections shared by each art journal in our corpus with other journals.

--

In addition to illustrating a historical or critical statement about the artist, the reproductions made the artist known, thus increasing the possibility of selling his works.

But was circulation always effective in making a work of art successful?

Some images, among those that the machine brings back to us, have acquired a canonical status today. Others have been relegated to the background, whereas their iconographic fortune in the past was certain.

Our corpus is not yet, and will never be complete. But it is already possible to identify certain works that have circulated much more than others since the 1880s in the illustrated press. Many have been forgotten.

The works most seen in the past are not the most known today, even for art historians.

It is exciting to discover what people of the past liked and saw, and which we have forgotten today. These images of the past sketch a visual history of the international tastes of a certain elite consumer of art images, images that crossed certain borders more than others.

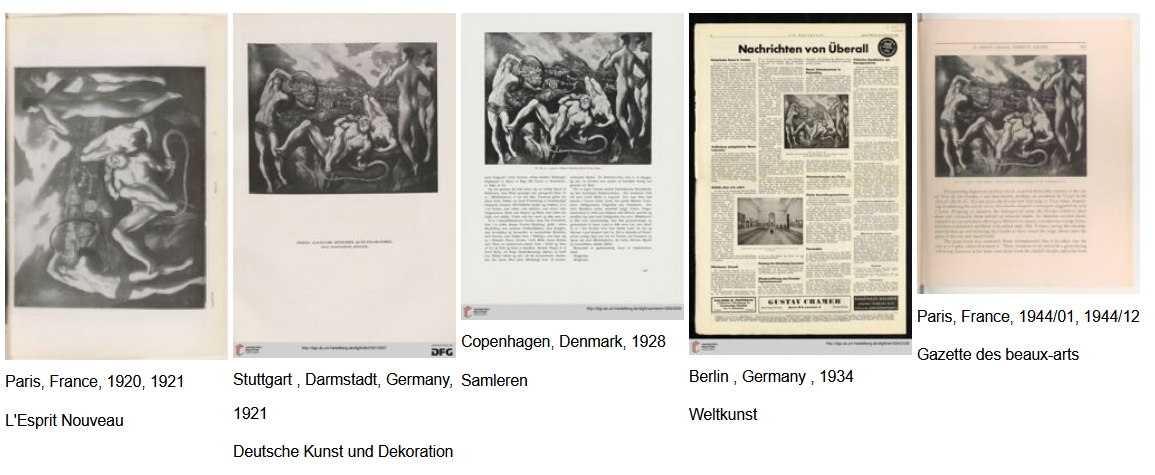

We present, in a digital exhibition for Europeana (https://www.europeana.eu/en/exhibitions/the-images-that-shaped-europe), the 100 most international groups of art images for the period covered by our corpus (1890-1950). These illustrations were collected by our machines in the spring of 2022, within the three million images recovered from the considered prints.

The ranking of the "top 100" is only indicative; this "Top 100" will probably be relativized by the next extension of the corpus. From a statistical point of view, however, it remains revealing of the preferences of an era - more exactly, of the artistic tastes reflected by the European and North American periodicals of the first 20th century.

--

The first 100 artistic images of the corpus

--

The first 20 artistic images of the corpus

--

The first 3+2 = 5 artistic images of the corpus

The first 100 gather many old works.

Nothing tells us that their reputation was made thanks to their reproduction in the illustrated press of the first 20th century.

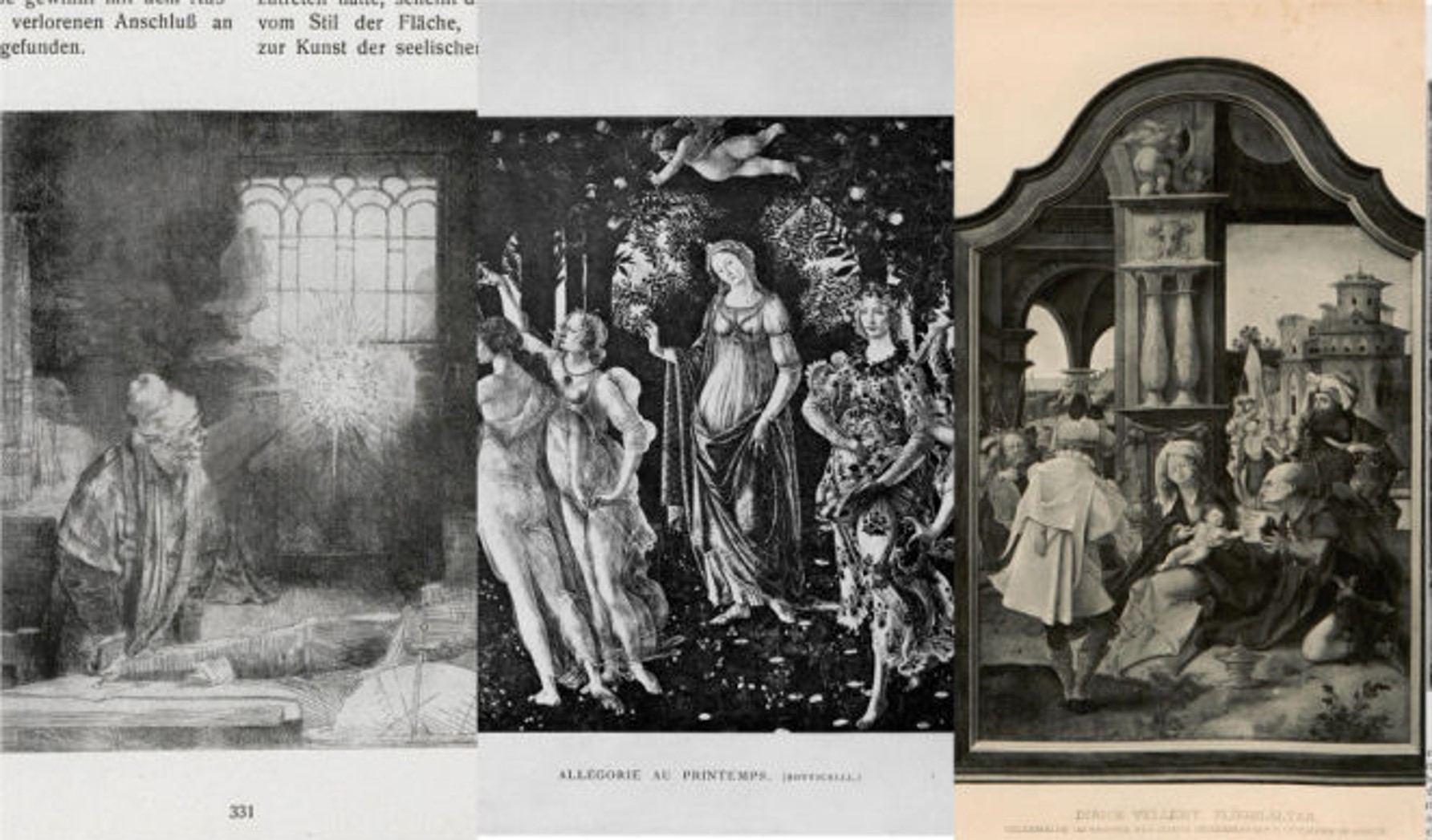

Among the authors of the "Top 20", in particular, we find familiar artists, whose works had been circulating in prints and copies for a long time: Albrecht Dürer (whose name appears five times, that is to say for 5 works in international circulation), Sandro Botticelli, Giorgione, Leonardo da Vinci, Vermeer, Rembrandt, Jean Fouquet, Rogier van der Weyden... These artists are what we still call old masters today.

But it is the turn of the 20th century that rediscovers them.

The 1890's were passionate about Botticelli, while the 1900's were enthusiastic about the German, French or Flemish "primitives". Art critics assigned to these artists national qualities that were highly prized before the First World War - especially for certain painters over-invested by patriotic circles. Rembrandt, in particular, was the object of much attention in the German-speaking countries at the beginning of the century[2].

--

Rembrandt (1606-1669), Doctor Faustus in his studio, engraving, c. 1652. Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Blot. Musée du Louvre, http://www.louvre.fr

Doctor Faustus in his workshop, an etching by Rembrandt (1606-1669) made around 1642, is the image with the highest total score. Today, this etching can be found in the Louvre à Paris and at the Uffizi in Florence.According to our corpus, the reproduction travels from 1840 to the present day (180 years), from the Netherlands and Germany to France and Poland.

This circulation of illustrations of Goethe's Faust I, published in 1808, is not unique to illustrated periodicals, as Evanghelia Stead has shown [3].It began with the first edition of the book, and contributed to the reputation of the work, which was soon considered one of the major works of world literature. From the 1850s on, new editions of Goethe's Faust were systematically illustrated. A generation later, magazines took over, or rather amplified the dissemination through images of a story that had become unavoidable.

The worldwide circulation of certain images accompanied that of stories and myths already conveyed by literary illustration.

Other images, in this Top 100, have acquired the status of icons, present even in everyday life.

Sandro Botticelli's Spring has transcended periods, boundaries of styles, reproduction techniques and cultures. The image can still accompany you at breakfast, on a T-shirt, a bag, or the cover of a notebook. Although many people will hardly be able to identify the original painting, let alone its author, Spring is part of a vast Western imaginary museum that already in the early twentieth century had occupied many artists who came to Florence to learn painting, spending hours copyng the master.The image is one of the many Déjà vu that a person may encounter in the course of his visual experience.

--

Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), Spring, tempera on panel, 203x314 cm, Florence, Uffizi Gallery

--

Botticelli's Spring, an object of great consumption

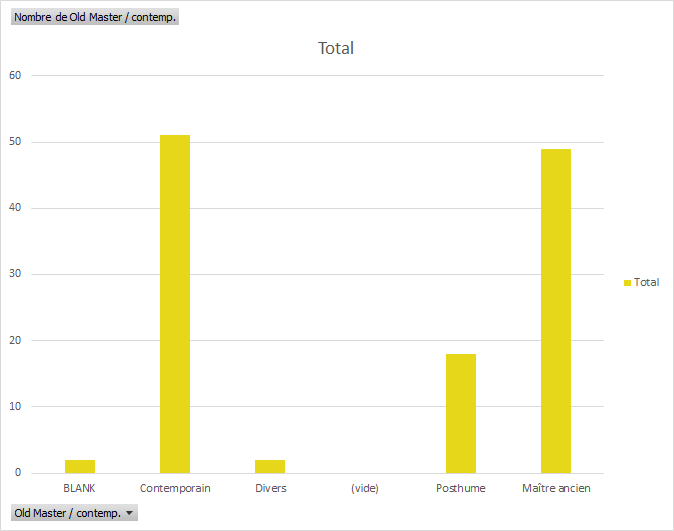

Does one circulate better when one is dead?

--

Édouard Manet, Music in the Tuileries, 1862, oil on canvas, 76 x 118 cm, National Gallery, London.

From a basic statistical point of view - limited, of course, to the first hundred artistic blockbusters in our corpus of images - it is quite clear that of the total number of works most reproduced in our periodicals, the majority are by authors who have been dead for some time, or even a long time.

The works of some modern painters seem to have had to wait for the death of their author before being reproduced in magazines. Thus for Edouard Manet; for Hans Sandreuter, Alfret Stevens, Henri Fantin-Latour and Pierre Puvis-de-Chavannes, or for John Everett Millais, Paul Cézanne, Georges Seurat.

It is possible that works by these artists have been reproduced more often than our corpus asserts - we are only talking about the first 100 clusters, our algorithms do not identify everything, and the corpus will always deserve to be increased. But one thing can be affirmed:

when you are dead, you are obviously less scary.

Perhaps this is because an artist who is too different from the others, once dead, will not risk continuing to innovate. Or rather: one is all the less frightening because what could be considered scandalous at one time has had ample time to be accepted.

In 1903 came the first instance of a reproduction of Monet's Déjeuner sur l'Herbe, a painting that predates the French painter's debated Impressionist period. Monet had then had ample time to be recognized by the market, by critics, as well as by his peers.

Edouard Manet, author of a Déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863) which was particularly controversial at the time of its exhibition at the Salon des Refusés in Paris in 1863, is not represented by this work but by compositions in which the women are dressed, wise and without provocative looks. Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe does not appear in our corpus until 1908...

Even after the death of the artists, the magazines seem to have preferred to reproduce their less dangerous works.

The works of deceased artists are also better distributed because the market is better for them. The death of an artist brings his career and production to an end, so it promises dealers that a drop in prices is unlikely.

The death of an artist also marks the beginning of his or her legend.

If he died young, he is regretted; if he died old, he is celebrated; if he died poor, he is made to feel guilty.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Symbolist generation even cultivated the myth of the misunderstood prophet - Vincent Van Gogh and his suicide was the object of this posthumous investment more than the others[4]while his contemporary Paul Gauguin took advantage of his exile to work on his own reputation[5]. Writing to him from Paris when the artist had moved to other latitudes, his friend Daniel de Monfreid understood him perfectly:

"You are at present this unheard-of, legendary artist who, from the depths of Oceania, sends his disconcerting, inimitable works, definitive works of a great man who has, so to speak, disappeared from the world; your enemies (and you have a good number of them, as do all those who bother the mediocre) say nothing... you are so far away!... In short you enjoy the immunity of the dead. You have passed into history[6]."

In our corpus, the images of living artists are very well represented. They are even those that circulate on the most international scale.

But by "living artists", "contemporary" - or "modern" -, what do we mean? Nothing very avant-garde, if we look closely at what is circulating at what dates.

--

Claude Monet, The Lunch, 1868, oil on canvas, 231.5 x 151.5 cm, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main

--

Ilya Repin, The Zaporogues Cossacks Writing a Letter to the Sultan of Turkey, 1880-1891, oil on canvas, 2.03 x 3.58 cm. Russian Museum, St. Petersburg

--

Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Tivoli. The Gardens of the Villa d'Este, 1843, oil on canvas, 43.5 x 60.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, Paris

--

John Everett Millais, Christ in His Parents' House, 1849-50, oil on canvas, 86.4 x 139.7 cm, London, Tate Britain.

--

Max Liebermann, Old Men's Hospice in Amsterdam, 1880, oil on wood, 55.3 x 75.2 cm, Sammlung G. Schäfer, Schweinfurth

--

--

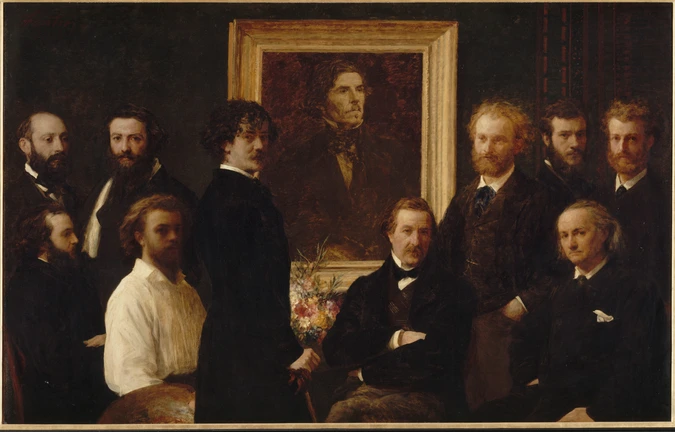

Henri Fantin-Latour, Hommage à Delacroix, 1864, oil on canvas, 160 x 250 cm, Paris, Musée d'Orsay..

Very discrete images...

Among the artists who produced these works, a good number were part of what has been called the cosmopolitan elite of modern art at the turn of the century[5].The images that illustrate their work are not the most scandalous, at the time they are reproduced. The press shows acceptable, recognized works, generally exhibited in the great international Salons of the time, or known for a long time because they have been seen and reviewed in Salons, galleries, in prints, or in important collections. Even for Picasso, the works that circulated during his lifetime were primarily reproductions of paintings from his blue period, from the early 1900s. At that time, the Spanish artist painted in a softened symbolist style that contributed greatly (paradoxically) to the success of Cubist painting.[1].

From article to poster. When the press forged icons.

What was, finally, the role of illustrated periodicals in the construction of artistic reputations? Was it only to soften reputations that were too sulphurous, or to make acceptable what might not have been? The reproduction of the works was certainly also useful to familiarize the readers with the work of the artists

In particular, our algorithmic clusters show that when certain images appear several times to illustrate press articles, they are more likely to be chosen to represent the work as a whole of the artist concerned.

--

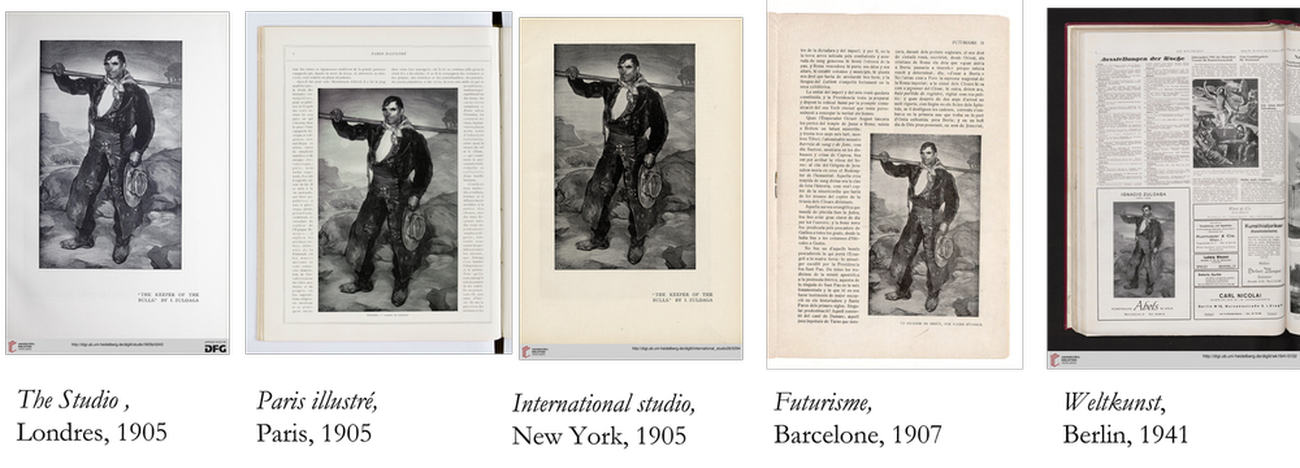

Here, Ignazio Zuloaga's The Bullfighter (date unknown) and James McNeill Whistler's Old Woman in Rags (1858) are both reproduced several times in history-related articles, before becoming the main feature of posters for sales or exhibitions held decades after the work was first reproduced in an illustrated periodical.

--

Softening images was also perhaps the best recipe for making them icons.

As for the artists, they were well aware of the value of reproducing their work in magazines.

In 1921, the critic and artist Georges Turpin published an artistic strategy with the clearest words:

"Magazines (...) serve as a very serious means of propaganda because they widen the field of prospection and prepare the opening of new markets. French artists obviously have a considerable interest in spreading their names and their works abroad. The most certain means is the diffusion of these by the reviews and particularly by those publishing articles illustrated with reproductions" [7].

Références

[1] Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, « La construction internationale de l’aura de Picasso avant 1914. Expositions différenciées et processus mimétiques », Revoir Picasso ; actes du colloque du musée Picasso, Paris, mars 2015 ; publié en ligne en mars 2016, texte et retransmission vidéo : http://revoirpicasso.fr/circulations/la-construction-internationale-de-laura-de-picasso-avant-1914-expositions-differenciees-et-processus-mimetiques-%E2%80%A2-b-joyeux-prunel/

[2] Michela Passini, L’oeil et l’archive. Une histoire de l’histoire de l’art, Paris, La Découverte, 2017. George L. Mosse, Les Racines intellectuelles du IIIe Reich, La crise de l'Idéologie allemande. Calmann-Lévy, 2006.

[3] Evanghelia Stead, Extensive and intensive iconography (Goethe’s Faust I outlined), conférence dans le cadre du colloque "The Circulation of Images", En ligne, 15-18 juin 2020 (Université de Genève, projet FNS Visual Contagions, et Ecole normale supérieure, Centre d'excellence Jean Monnet IMAGO).

[4] Nathalie Heinich, La Gloire de Van Gogh. Essai d’anthropologie de l’admiration. Paris, les Éditions de Minuit, coll. « Critique », 1991.

[5] Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, Les avant-gardes artistiques. Une histoire transnationale, vol. 1 1848-1918, Paris, Gallimard, 2016.

[6] Lettre de Daniel de Monfreid à Paul Gauguin, vers 1901-1902, citée par Sophie Monneret, L’impressionnisme et son époque, Paris, Robert Laffont, 1987, t. I, p. 284.

[7] Georges Turpin, La Stratégie artistique – Précis documentaire et pratique suivi d’opinions recueillies parmi les personnalités du monde des arts et de la critique, Editions de l’Epi, Paris, 1929, p. 115.