Our corpus' bias

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel & Nicola Carboni

It is not enough to have assembled a global corpus to be satisfied with the 'data'. What is 'given' to us is never available by chance.

Geopolitics of digital corpora

The first bias is that of the exhibition catalogues that we have been able to recover from one year to the next. Most of them are French-speaking - because the team is French-speaking;

and because the libraries where we find our catalogues are those that are most accessible to us. We are working with partners in Brazil, Japan, Croatia, Germany, the United States and Spain to fill in the gaps; this will take time - the digitization of documents will help.

The second bias is that the geography of illustrated periodicals available on the web reflects the imbalances in the global geopolitics of culture.

--

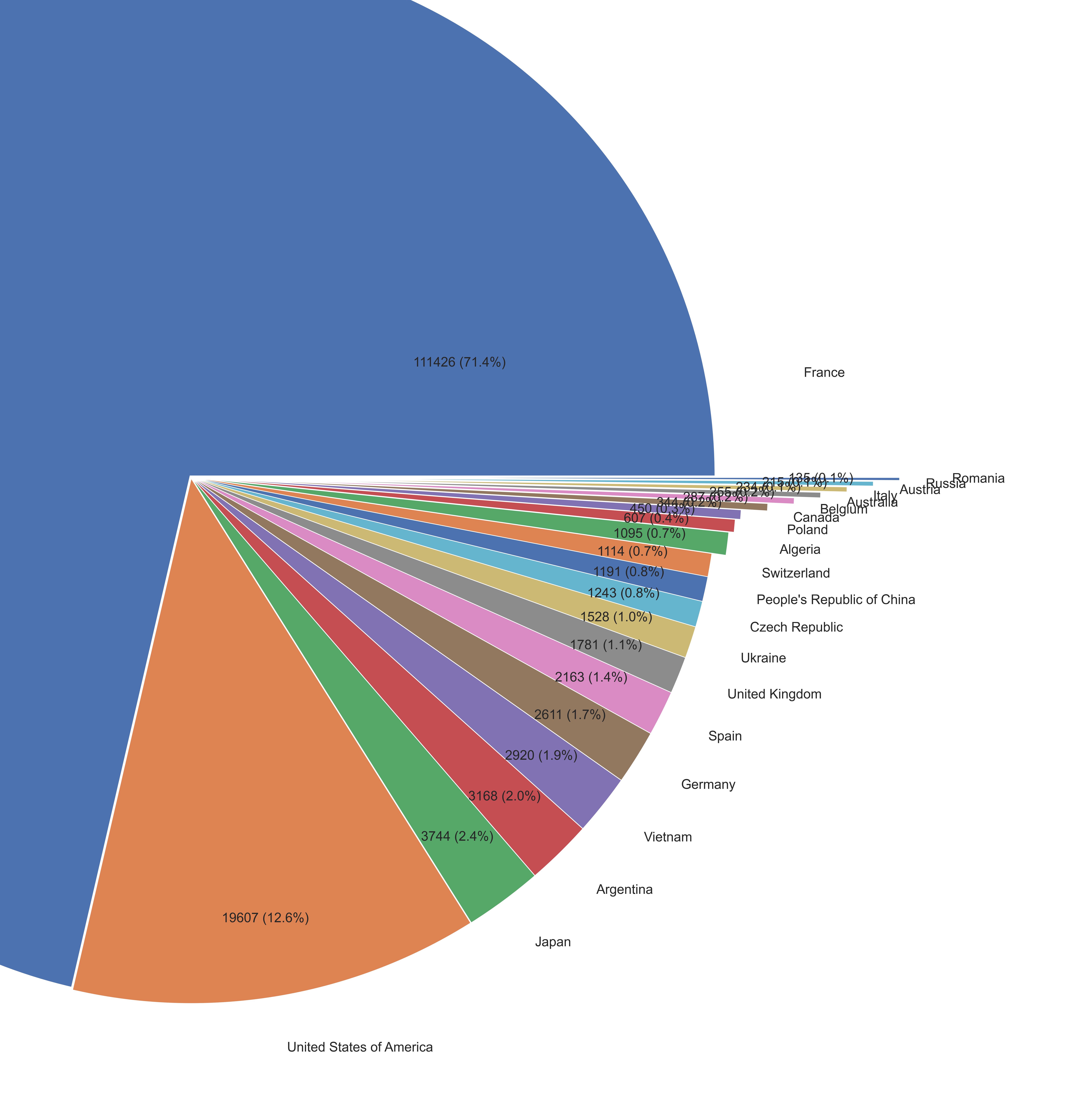

The sources of illustrated periodicals explored by the Visual Contagions project, as of April 2022.

Share of the top 20 countries represented (total number of countries: 121).

Some countries have the means, techniques, skills and political will to digitize their printed heritage. Others do not. For example, the Visual Contagions team has been able to find sources online faster and earlier from Europe and North America. In May 2021, the vast majority of sources gathered were North American: the most accessible sites are American. This imbalance has been modified in favor of the French-speaking world with the inclusion in the corpus, at the beginning of 2022, of a large collection of documents digitized by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Thanks to this collection the corpus, although now predominantly French, has been extended to the former countries of the French colonial empire, from North and West Africa to Vietnam.

--

Above: Interactive mapping of the sources analyzed by the Visual Contagions project (as of May 2022).

--

The over-representation of North America and Franco-German Europe has as a corollary a glaring lack of sources from Latin America, Africa and Asia, but also from Southern, Northern and Eastern Europe. We are working to fill these gaps, although it is almost certain that the quantities found will never be complete.

Despite these imbalances, the sources currently collected are spread throughout the world, and not in negligible quantities. This may lead to the hope of finding images that have rotated between countries, cultures and eras.

Even if we will never be able to give a definitive answer to the question: "Which images have circulated the most around the world?", we have the means to identify some that have circulated a lot. We must forego exhaustive or definitive results in advance; although it is quite clear that the representativeness of our results will always be more important than that of traditional studies.

We often don't get permission

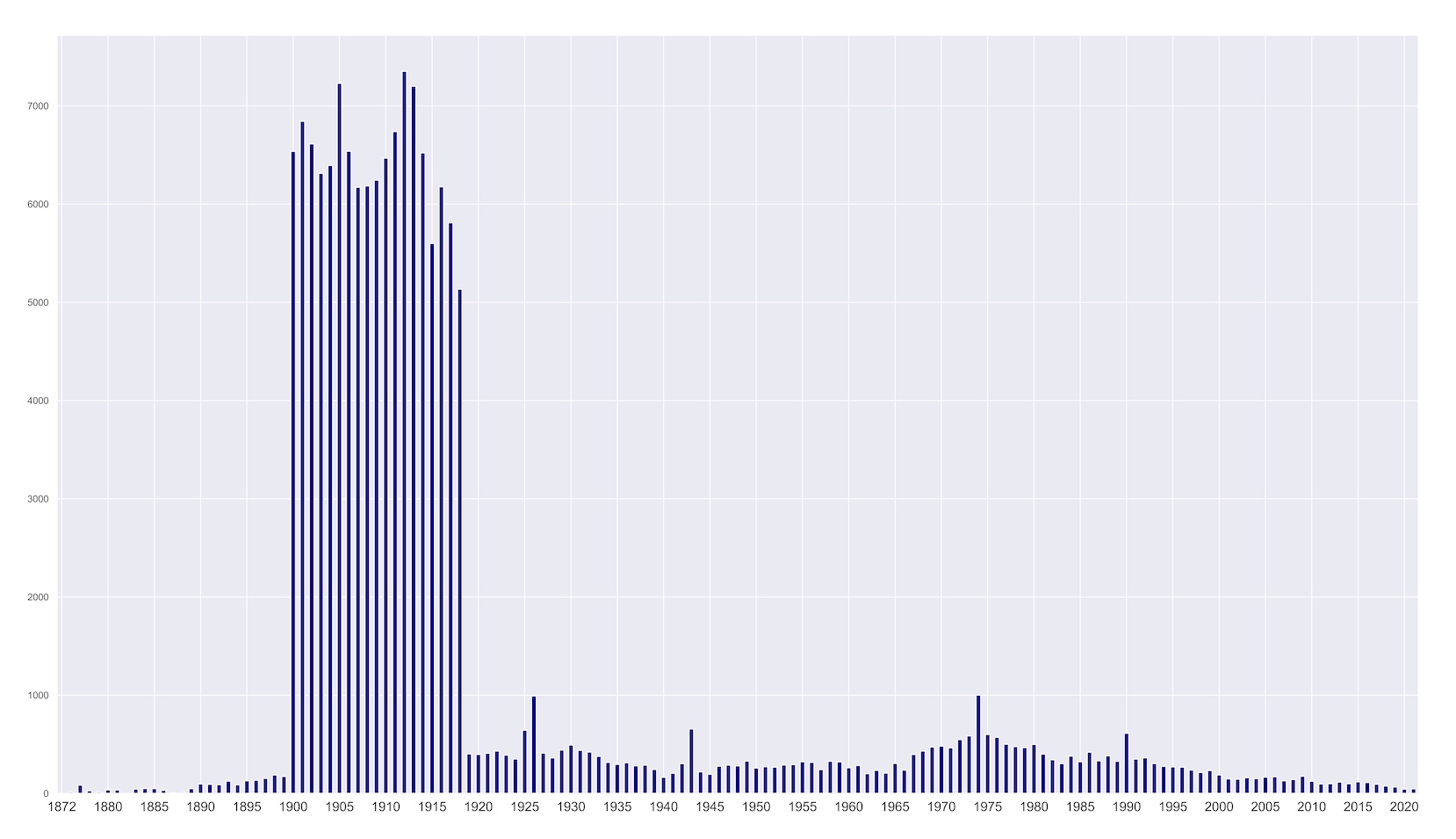

Another bias that will always structure our data is the law. The chronological distribution of our documents reflects the legal conditions of their availability.

Because it is not because an institution has all the collections of Paris Match that it has the right to put them online. Nor because Der Spiegel puts all its covers online does it mean that we have the right to use them.

Most of the sources currently available to the project are from the period before 1950 (although some images published before 1950 are still under copyright). For this period, image rights do not require us to respect the wishes of any rightful owners, nor do we have to pay royalties for the reproduction of images to their 'owners'.

What saves us: the right to analyse web data.

It is allowed to go and look for images, magazines or posters on certain sites and to study them, without redistributing them. We are therefore working, especially for the period after the 1950s, 'in private' on globalisation through images. We will publish the results later, contacting the rights holders of the images we want to show to our public.

--

Chronological distribution of our documents as of May 2022

--

Where and when? Sometimes uncertain or missing information

The last structuring bias is the way our sources are described.

Our sources are sometimes poorly described. We do not always have a clear idea of where and when certain documents and their images were published, seen or created - especially for artworks and posters.

Fortunately, some of the collections have been compiled as exhaustively as possible.

This is the case for the journals made available by the Gallica database of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, or for the collection of avant-garde journals at Princeton University. Other collections, such as the artistic images available in Wikidata, are incompletely described.

Thus, the problems associated with source information cannot be defined solely in terms of completeness.

The incompleteness of the date and place information may be an effect of the history, an element to consider in our analysis.

Not everything has a date, and not all dates are accurate.

The historicity of sources implies an uncertainty about the date of publications, which is inversely proportional to the circulation and potential audience of the documented source. A small arts publication created in Berkeley in the late 1960s may be extremely important for tracking visual changes within the counterculture movement, but may lack all the classic bibliographic information. The same can be said of underground publications, distributed in a country without giving an official address, for obvious reasons. This is the case of many publishing products published in Europe during the Second World War.

Finally, tackling a global corpus means dealing with a wide variety of languages and alphabets.

London, Londra, 倫敦, or Londres ?

The issue of languages does not only affect our understanding of sources; it also has consequences for the way we describe a source.

The possibility of understanding and documenting these numerous sources is only possible with a multilingual team, in addition to the help of existing translation applications.

Лондон? Llundain?

Random finds, unexpected agreements with new institutions or illustrated magazines still in operation, help and proposals from colleagues in foreign countries (particularly for China and Japan), digitization campaigns when possible... Visual Contagions is a long-term project, which will yield all the more results if it involves numerous international collaborations.

In the meantime, the team has collected documents from all continents.

This is a pretty good start to tracking the global circulation of images.

Read more :

When there is not enough room in the oven...

Go back :

In the project's kitchen

Chapter :

II. Promises of the machine