Experiment

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

The Visual Contagions project is largely experimental - we are trying new approaches on larger corpora than ever before, with the risk of getting lost (as with any experimentation) in the twists and turns of inventing a method, repeated tests to improve our processes, or results too numerous for a simple and clear interpretation. If the process is sometimes a bit frightening, it is also exciting. Beyond a naive claim to objectivity, we are more aware than ever of how much research is subject to chance, to the small pleasures of unexpected discoveries. Our project is an experiment, and we must assume the consequences as well as the promises.

We experience experimentation above all in the choice of our analysis tools, the testing of successively disappointing or promising visualizations.

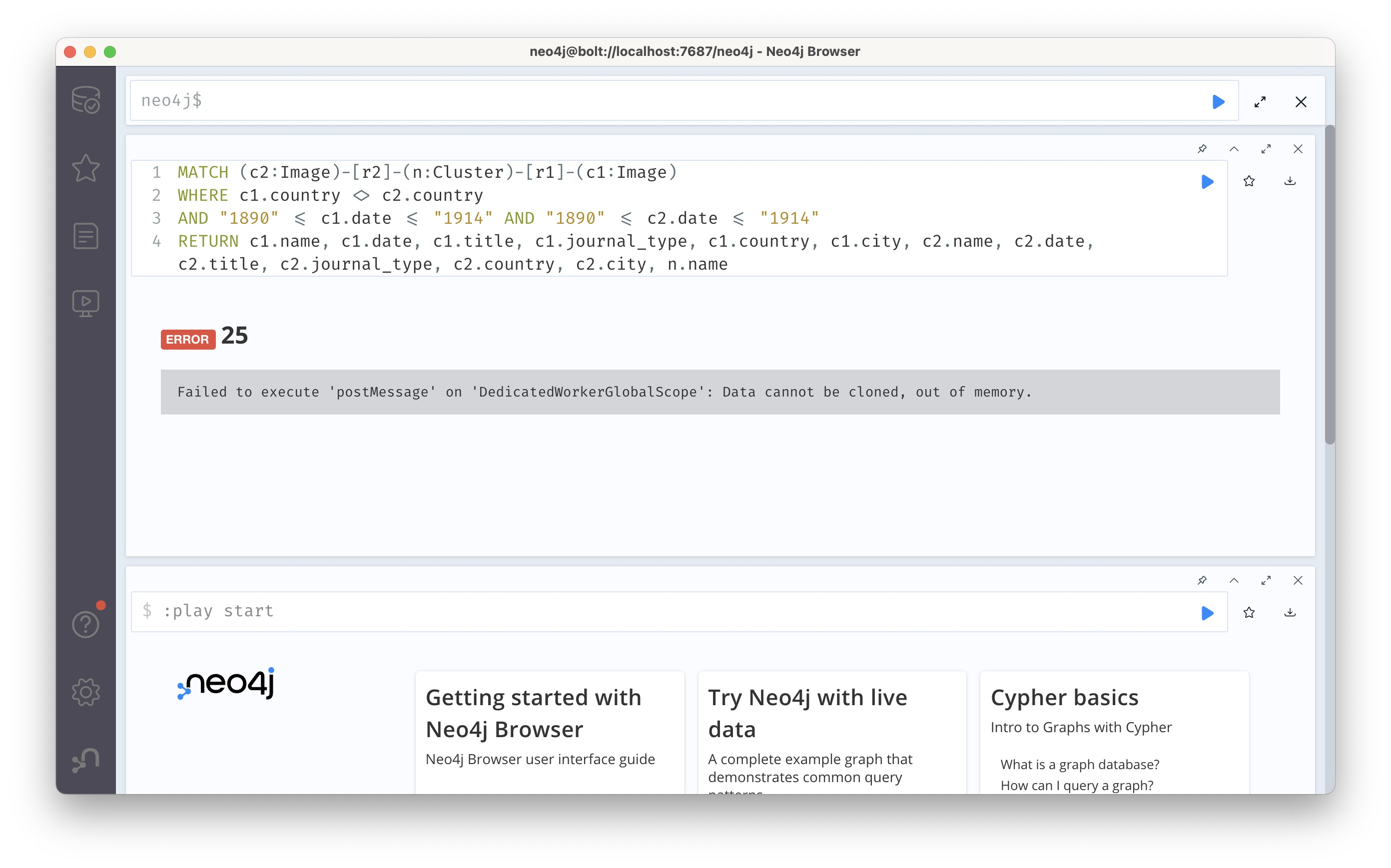

It is often necessary to trick our machines: the more the database increases, the less the memory is sufficient.

So we cut the database in pieces to try less heavy visualizations, we separate the images by type, the magazines by period or by country. This is science: like in the laboratories. We try every possible solution to approach a phenomenon as closely as possible.

Hence the importance of multiple trials and crossed points of view.

--

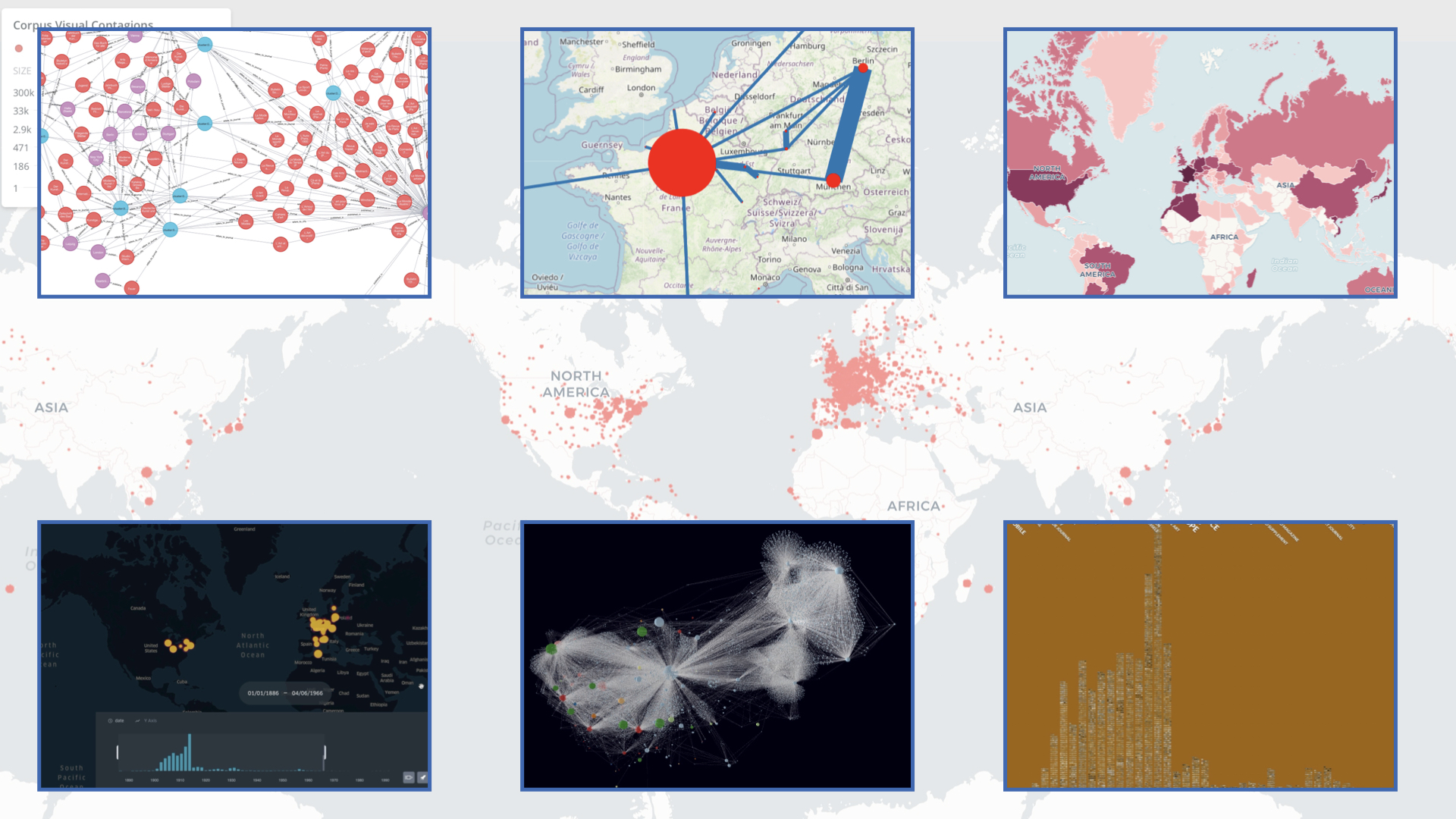

Different reviews and visualizations of the Visual Contagions corpus.

Top left: graph of journals that share images with journals from other countries.

Top center: axes of circulation of images in Europe

Top right: geographical coverage of the corpus

Bottom left: spatio-temporal projection of the journals

Bottom center: interconnections between journals and images

Bottom right: image by year of publication with keywords

Experimenting, on the question of viral images, is also to look at how images circulate today, before wondering about what has changed - and what has not.

We often have the opportunity to observe a very contemporary visual circulation: that of memes.

It can inspire our work - if only to note, often, how things have changed, but also that the printed circulation of images has been able to take place in ways similar to memes.

The concept of meme extends the memetics of Richard Dawkins, a biologist and evolutionary theorist, to contemporary digital communication networks. The meme designates a viral and dynamic object, which is both a product and an explanation of contemporary culture.

For today's visual blockbusters that are memes, virality is a permanent state.

The image, in the case of memes, is no longer valid as a unique and individual image, but as an element of a series, in perpetual evolution;[1]; indeed, as an element in the process of becoming multiple, a viral propagation likely to become self-referential.

The images of which memes are made circulate by varying each time a little bit: a slightly different text, a word more or less, an additional bubble, a modified character...

The image, in the memes, is not a static object but a dynamic element which adapts permanently. The meme is thought to create new meanings through the text or the paratext, while keeping a common reference, in order to create a complicity with those who will receive it.

In this new form, the cultural and digital blockbuster is declined and gives birth to viral and transmissible avatars.

The phenomenon of memes is not recent, even if our digital era has accentuated it and made us aware of its existence.

Repertories of images such as Cesare Ripa's Iconology in the 1600s were the basis of local iconographic references and variants. Paintings by Piero della Francesca, Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino are found mixed in Pasolini's films after the Second World War[2]. The digital DNA of memes must be considered as a gas pedal of the circulation and mutation of images, a factor of democratization, but also a tool of conversion fed by irony[3].But in the non-digital regime, too, there were memes - or phenomena close to what we consider memes.

Is the digital indispensable to the meme? This is not certain.

It is true that new viral forms most often develop in digital channels. However, in many cases, their power of communication is so great that their impact is physical - in the sense that it is played out on non-digital modes of image circulation. This is the case of the short-circuit between the image and the film. Certain films, or rather certain film scenes, have become the subject of a meme, condensing the scenario into a single image. The scene is densified in a simple frame, whose circulation makes iconicity. The iconic image that carries the meme develops, changes, reappears in a series of meanings inextricably linked to the film. A media short-circuit forces a connection with the film, and changes the way we consider it.

Anyone who is familiar with pop culture and the Internet will probably remember, when looking at the figure above, the movie that each image summarizes, the scene, the name of the character, the scenes that precede and follow. But he will certainly remember, and even more immediately, the memes that sprang from these images. Seeing one of these films again will be a new experience - a mix between the content that the director chose to convey and the content that has been associated with the scene through the memes. Perhaps the viewer will laugh at the jokes in the memes; perhaps the meme's presence in the viewer's memory will prevent him or her from really enjoying the film; in any case, each viewer who knows the meme will have a different and new experience of the film.

The phenomenon of memes may appear as a simple derivation of a cultural product, but it is much more complex.

A contemporary example of this virality is the meme created from Morbius, a Sony film released in 2022. This film was the source of a large number of memes that, using invented phrases that never appeared in the film, mocked its seriousness as much as its epic nature. These memes were not produced from the film; they are not based on the film and do not condense it. In this case, the process of creating the memes was transformative. The scenes that circulate are extrapolated and contain no reference to the film. They only use the film as a palimpsest, on which one rewrites several times without caring about what was written before. The character of the meme is simply given catchy little phrases, invented as needed. The attention is diverted from the film and the image does not rewrite the film. If there is indeed virality, no media short-circuit that would rewrite the scene comes out of the process. How can this be explained? Most likely, the scene has not been seen by those who reuse the meme and re-circulate it. The Morbius meme is just a tool of mockery, of ridicule. As a proof of this, memes about the movie appeared before the movie was even released in theaters (see the google trend below, as well as the detailed description of the meme on the knowyourmeme site)[10]

In this case, it is no longer a question of rewriting a film scene, but of writing it, which almost replaces the original work. We are not really witnessing a process of referencing, but rather an erasure of the film; a celebration, a productive ironic homage, which could have a favorable impact on the film.

This ironic homage, paradoxically, was not grasped by Sony: when the film was re-released for a second run, Sony hoped to capitalize on the Internet culture. The firm had to withdraw the film after three days.

The latest example of the reuse of a viral image, that of a pop culture icon: Spider-Man.

Figure 3. “Spider-Man Pointing at Spider-Man”. Scène from episode 19b from the 1967 cartoon "Double Identity"[11].

When Spider-Man meets Spider-Man, ... today the image has become a meme, suitable for producing new stories.

In this case, the original image is that of a Spider-Man cartoon, of which an episode from the 1960s features two Spider-Men: the original and its copy. This image has become famous in recent years, so much so that the producers of the 2022 film (Spider Man: No Way Home) have reused it. The new scene, close to the one in the cartoon, makes a clear reference to it, even if it is part of a different story. In 2022, Spider-Man no longer meets his doppelganger but himself, in multiple versions of the past. The objective is to refer to the meme, while giving it a new meaning, a new objective. This objective is so clear that from the beginning of the film's promotion, Sony's marketing team produced a specific documentary on "The Making of the Meme" based on this example[12].

What do these examples tell us? They suggest that we try (experiment) with new interpretations when we encounter viral images from the past.

The common features of today's memes and some viral images of the past could be the following:

1. Today's successful images circulate all the better because they carry shared references, the obvious elements of cultural communities.

2. Memes make people laugh. They sow irony.

3. Their circulation is intermediary. Memes go from cartoons to social networks, from social networks to movies, from movies to video games or T-shirts, derivative products as well as private productions. Yesterday's memes?

4. Last, but not least, the suggestive dimension of memes is constitutive of them: the meme triggers a story, it opens a whole world.

It is in this spirit that the artist Nora Fatehi has produced a meme machine.

A way for us to become a meme, to be part of the mosaics that make up the imagery of the internet. Reusing predefined memes, she has broken down their structure by inserting the participant into the viral. The artwork is responsible for the confrontation between Internet pop culture and traditional exhibition viewing, resulting in a series of reactions that demolish the premise of the meme itself. The meme thus becomes the reflection of the incomprehensibility of the meme itself, the clash of generations, losing the aura of irony that characterizes it to develop a totally new effect.

#visualcontagions pic.twitter.com/t6iyMdSEzI

— you and meme (@norabot1) June 2, 2022

— you and meme (@norabot1) May 10, 2022

#visualcontagions pic.twitter.com/eLSmNxDpVa

— you and meme (@norabot1) August 20, 2022

[1] Lewens, Tim, « Cultural Evolution », The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (édition d’été 2020), Edward N. Zalta (éd.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/evolution-cultural/>.

[2] S. Maffei, "Introduction", dans S. Maffei & P. Procaccioli (dir.), Iconology, Turin, Einaudi, 2012.

[3] M. A. Bazzocchi & R. Chiesi et Pier Paolo,Pasolini, Électrocutions figuratives, Bologne, Cineteca, 2022.

[4] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/for-the-better-right

[5] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/joker-stairs

[6] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/some-men-just-want-to-watch-the-world-burn

[7] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/condescending-wonka-creepy-wonka

[8] https://knowyourmeme.com/memes/one-does-not-simply-walk-into-mordor

Read More:

1. Characterize. Is a circulation of images necessarily epidemic?

2. Describe. Where, when and how fast? How?

3. Explain. Are there laws of imitation for images?

4. Experiment.

Next Chapter