Specters of Aby Warburg

Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel

Our working tools are haunted. The Visualcontagions/Explore platform is, strictly speaking, what we call an atlas. Images are presented as if on a board, one next to the other, with minimal captions. With these illustrations, mostly in black and white, the platform carries the memory - or the haunting - of another atlas, so well known, too well known in art history: Aby Warburg's Atlas Mnemosyne[1].

--

Partial view of a cluster of nearby images reported by VisualContagions/Explore.

Hovering: sheets of images arranged in panels in Aby Warburg's library in Hamburg, early 20th century.

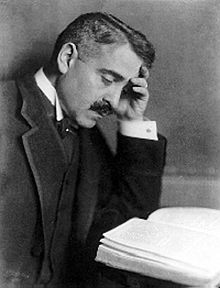

Warburg was a researcher fascinated by what images carry

–of gestures, joys as well as individual and collective anguish, sometimes the strange memories of a distant past. He scrutinized, in the circulation of forms, what he called formulas of pathos (Pathosformeln): bodily attitudes that became visual motifs, capable of transporting, over generations, the memory of ancient times, and with them hauntings and hatreds as much as the noblest of attitudes.

Born in 1866 into a large Jewish family of bankers in Hamburg, Germany, Aby Warburg refused to take over the family business and instead devoted himself to his research on the history of art and civilizations. He left the business to his younger brother - but with one condition: unlimited means to build a library.

This renunciation of power and wealth for the sake of art history is enough to make Warburg a fascinating figure for art historians. But the character also impresses by his psychiatric fate, and the place that art history occupies in it.

Prone to nervous disorders since childhood, Warburg became so distressed after 1918 that he threatened his family and had to be institutionalized. His means allowed him to be treated from 1921 onwards by the psychiatrist Ludwig Binswanger at the Kreuzligen Clinic in Switzerland. Warburg was the object of attentive care, which his doctor recorded in notes that historians are still commenting on today[2].The gradual resumption of his scientific activities, with the help of his assistants Gertrud Bing and Fritz Saxl, seems to have helped cure his schizophrenia. After the success of a conference on the rituals of the Hopi Indians, on which he had accumulated a wealth of ethnographic documentation during a trip to the United States in 1895-1896, Warburg saw his condition gradually improve. In 1924, he was able to leave the clinic and began to devote himself to a new project: a vast atlas of images, which he called Bilder Atlas Mnemosyne. The project was cut short by the death of the art historian in 1929. But his legacy was not lost.

The Mnemosyne Atlas: a new approach to the circulation of images

The atlas represented a new relationship to images that has been the subject of much discussion.

Warburg had scoured Italian archives, surveyed ancient sites and museums, studied exotic populations in America, and owned (and read) an impressive collection of books on the most varied areas of the history of civilizations. But he also used a large photographic collection for his comparative research[3]. The historian compared, arranged and rearranged these pictures according to his questions and findings. By compiling them in this way, he studied the circulation of visual themes from Antiquity to the Renaissance and even to his own time. The plates were also used for workshops and conferences, installed in vertical panels or laid flat on work tables. It was on the basis of this method that Warburg wanted to realize the Mnemosyne Atlas project.

However, the plates arranged in an arc in the Kunstwissenschaftliche Bibliothek in Hamburg also made it possible to make new visual comparisons.

To make, like Warburg, an atlas of images, soon became the disposition par excellence of art historians who wanted to "let the images speak" and find inspiration in unexpected, almost surrealist connections.

--

A board from Aby Warburg's library in Hamburg.

In addition to recognizing the comparative utility of the atlas - the basis of any research into circulating forms - art historians are even more interested in the way Warburg, through his way of arranging reproductions, elicited and sought unexpected echoes and dialogues between images.[3]. His approach is all the more appreciated when the effects of the classical art historical method - dating, locating, attributing, materially describing an image and linking it to its context - have been exhausted.

Today, as in the past, Warburg's approach is most stimulating. The atlas has become to art history what surrealism is to painting.

At the time when the Hamburg historian invented this method, most art historians were bogged down in an ultra-detailed approach to their objects of study, not always informed by archives and context. Warburg, on the contrary, looked at images in a new way, both across time and space. His approach freed us from narrow aesthetics and chronological considerations, to consider more general questions about civilizations and humanity. It allowed to question the impact of forms, their role of cultural vehicles, as well as their cathartic functions.

In images and forms, Warburg sought wild energies as much as harmony or disorder as much as order.

He looked for forces that he himself suffered from. He was aware of this, since he noted that he was "trying to read through the 'image' the schizophrenia of the West, like an autobiographical reflex of sorts"[4].

Warburg did not, however, abandon the idea of taking into account archival sources, texts that shed light on past images, and any other elements of context. He showed that it was possible to productively articulate a formalist visual approach, the most rigorous historical science, and the freedom of a method in which the researcher lets the images speak through their comparisons, echoes and similarities.

If it took time for Warburg's heirs to understand that iconology would go further if it assumed the ambitions of its founder, the atlas approach has now become the norm.

Working by atlas seems to be considered, in these disciplines, as a method which can distinguish art historians more perceptive than others.

Since the 1990s and the great rediscovery of Aby Warburg, creating an atlas is a bit of a stylistic exercise; a choice capable of conferring on an academic work (which might be too academic), the touch of originality and intelligence that would place it above the others. One then comments on images divided into plates, à la Warburg, to let a meaning arise that their dialogue would say better than the traditional chronologies and connections. This approach continues to fascinate European art historians who are tired of historicism and its positivist pretensions, and who are no longer convinced by the French Theory that came back from America, which did not bring anything really novel to visual studies[5].

But if art history à la Warburg has been particularily productive lately, it can get, sometimes, rather verbose. Above all, the generation that carried it has taken on a tutelary, intimidating place in the European disciplinary field.

Warburg, commented and over-commented upon, has become an impressive spectre; and the atlas approach has taken on the weight of a canonical method, over-determined, with obligatory vocabulary and questions - like a categorical imperative.

To use an atlas is to "condemn" oneself to read Warburg, and with him his voluble commentators; at the risk of not being able to work freely anymore.

VisualContagions and the ghosts of the Mnemosyne Atlas

Our Explore platform has all the makings of an atlas. That's our problem.

--

atlas Cluster (https://visualcontagions.unige.ch/explore/duplicates/search/d0439516-bae0-488c-ad06-9cb81135419b/)

The atlas is a visual form. It can be found in our corpus.

Here, antique objects are associated with each other; there, a collection of stamps; elsewhere, the photograph shows a wall on which works of art have been hung; many times we find in this cluster views of a Salon or a painting exhibition. The Explore platform even brings together these arrangements of images in a grid, of comic book pages.

What do these connections tell us? That our approach is based on the same desires and anxieties as those of stamp collectors, archaeologists or comic book designers.

By working with atlases, we must be aware that we are manipulating a "formula of pathos", as Warburg showed in the circulation of images: a visual form that conveys desires, impulses, and ancient anxieties.

Collectomania, display mania, the drive for order

--

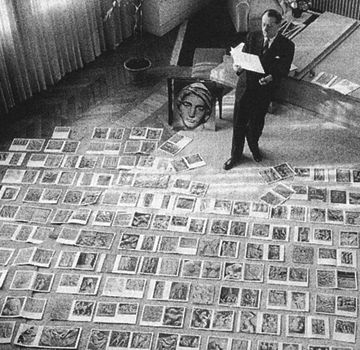

André Malraux at his home in Boulogne, March 1953. Photograph by Mauride Jarnoux for Paris Match.

Like stamp collectors, we like to handle a lot of images. Like them, we may need to display all the ones we have found, as much as to show our ability to have found them.

We are also taken by the same impulse to order what passes before our eyes; to extract, from a deluge of images, some waves that we could put down, understand, master.

The atlas is both an attempt to order too many images, and a fantasy of well-ordered playing cards.

On the side of order, it obeys the synoptic impulse characteristic of a scientific culture where one would be in control. It is like a dashboard - everything is gathered there for an efficient manipulation. On the fantasy side, the images arranged in an atlas often take on a narcissistic function: they reflect the mood, the tastes and the culture of each individual. There was a bit of this, for example, in the work of André Malraux on his "imaginary museum". If this approach is accepted, even socially expected in certain circles - as is the case for artists who today work with moodboards -, and if it has become widespread since the diffusion of digital image applications and their successful "personal walls" - from Flickr to Pinterest -, it is more troublesome in a discipline, art history, where the requirement of distance, objectivity and scientificity has been collectively internalized.

Summary archaeology

Like archaeologists, however, we need to classify our images according to precise logics - in this case, visual, chronological and geographical logics. But the approach would be relevant if we had as little information as archaeologists. As far as we are concerned, staying at the level of archaeology would not be serious. To link the visual form of the atlas, with which we work, to these forms which are close to it, is to become aware of certain risks to which the approach of the atlas exposes us.

In addition to the risks of the drive for order and narcissism, we run the risk of being satisfied with too little, whereas it would be possible to go further to reconstruct the contexts of production and circulation of printed images.

Comics and narrative impulse

Finally, by working by image plates, and what is more, with images ordered according to time and space, we risk succumbing to the reflex that makes us detect a story in a sequence of successive images.

But is there necessarily a story in a succession of images?

Do we have the right to deduce, from the spatio-temporal organization of images, that something would have circulated from one image to another? Do we have the right to tell a story from this sequence?

Thus the ghost of the atlas does not bring so much a clear message as a fear: that of the risk of letting oneself be carried away by the visual; of never going far enough in the historical contextualization, the search for concrete explanations to the circulation of a motif; of sometimes telling stories that would only be stories.

This anguish is the corollary of another, no less pressing, no less embarrassing: that of getting lost in the details; and of not saying anything interesting, engulfed as we are in the reconstitution of contexts.

What then does the specter of the atlas whisper?

Halfway between the Apollonian and the Dionysian, the individual and the collective, the general and the particular, the method and the improvisation, the toil and the nonchalance, the genius and the stupidity, the approach of the atlas will always be as productive as problematic. The atlas is a concatenation of too many forms, whose logic escapes us, but which can nevertheless be interpreted and told at leisure. The deluge of images can be all the more maddening precisely when we try to understand and order it. Or it is because we are "mad" that we try to put it in order and that we choose to work with boards and grids of images? The ghost of Warburg raises doubts. It is not certain that the history of art saves from madness. And even less, the approach of the atlas.

Notes

[1] Aby Warburg, The Mnemosyne Atlas, with an essay by Roland Recht, translated from the German by Sacha Zilberfarb, Dijon, L'Écarquillé/INHA, 2012.

[2] Ludwig Binswanger, La guérison infinie: histoire clinique d’Aby Warburg, Paris, Rivages poche/Petite Bibliothèque 716, 2011.

[3] Carole Maigné, Audrey Rieber et Céline Trautmann-Waller (dir.), La Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg comme laboratoire, Revue germanique internationale, 28, 2018.

[4] Georges Didi-Huberman, L’image survivante: histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg, Paris, Minuit, 2002.

[5] Aby Warburg, note of April 3, 1929, Tagebuch der Kulturwissenschaftlichen Bibliothek Warburg mit Einträgen von Gertrud Bing und Fritz Saxl, in idem, Gesammte Schriften, vol. 7, ed. Karen Michels and Charlotte Schoell-Glass, Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2001, p. 429.

[6] Béatrice Joyeux-Prunel, « Aby Warburg au-delà du génie solitaire », Revue d’histoire des sciences humaines, 37-2020, Nommer les savoirs, coord. Wolf Feuerhahn, p. 331-338. https://journals.openedition.org/rhsh/5528